Support the ABR Team

Help build a better experience for our ABR cycle team. We spend many hours on a non-paid basis.

What is Your Power - pt4

What is a cycle training plan and how to plan one.

A training plan will help put you on the fast-track to achieving that goal. If you ride with a power meter, a training plan will enable you to get the most of your time on the bike by giving you specific sessions to work on the weaknesses and build on your strengths. By now you will have a better understanding of the benefits of training with power, how to do an FTP test and what your training zones mean. Now we’re going to put all that into action by looking at how to create a training plan that works for you.

If you’ve got a goal, a training plan will put you on the fast-track to success. Entire books have been written on creating training plans – it’s not a simple process and ultimately every rider responds differently, so the process always needs to be tweaked and adjusted to maximize the benefits. It’s important that any rider understands the principles behind how a training plan is put together, in order to understand what they are doing out on the bike, whether that plan is set by a coach or not. We’ll take a closer look at the key principles behind a training plan, so you can understand how the riding you do has the effect it does.

Train, recover; train, recover

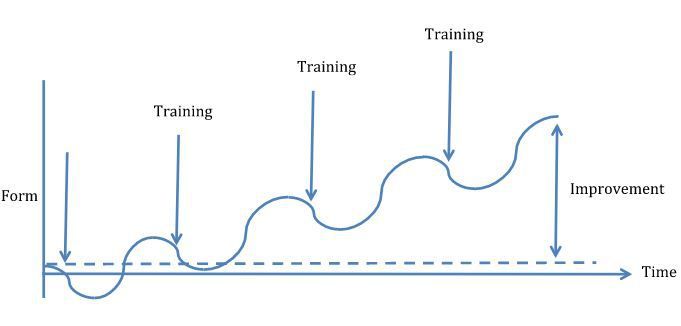

The ultimate aim when riding with a power meter is to become a better cyclist, and we all know that training makes you a better cyclist. The important things to understand, however, is that what is actually happening when you train hard is that you are giving your body the stimulus to improve – but you need to recover from each session in order for your body to adapt to the training and rebuild stronger than before.

After each training session you will see a small drop in form, but you will then build to a higher base. After a training session, you will feel fatigued and this leads to a short-term reduction in form. However, once you start to recover, your form starts to increase and, when you have fully recovered, you body will have adapted to the training session and become stronger, leading to an improvement in fitness and form compared with before.

This is the key principle which underpins any training plan.

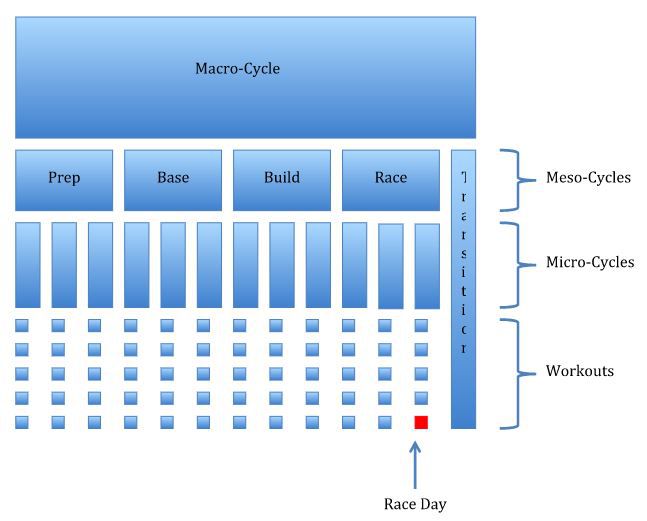

Each training block will see you build form over a period of time. In order to allow for sufficient recovery when training, you should use training blocks, which are essentially blocks of training sessions, separated by periods of recovery. The amount of recovery is dependent on how much fatigue has been accumulated during the training block. There are three different types of training blocks: macro-cycles, meso-cycles and micro-cycles. Together they make up what we will refer to as periodisation.

The macro-cycle represents an athlete’s annual plan, underpinned by the point(s) in the year the athlete’s goals are. The macro-cycle then shows how to best work towards those goals. For example, if a rider had major goals in February, June and November, the macro-cycles would be: from when they started training until February, from February to June and then from June to November. Following each macro-cycle a period of transition takes place where the rider can recover, before moving on to the next goal of the season.

Each macro-cycle is then broken down into meso-cycles, each of which works on a specific aspect of fitness. At the start of a macro-cycle, the meso-cycles tend to be quite general (for example, a meso-cycle focused on base training), however as the rider approaches a goal, the training sessions in that cycle will become increasingly more goal-specific. Meso-cycles typically represent a two to four week period and are in turn normally made up of five to ten micro-cycles.

I typically use micro-cycle lengths of between three and eight workouts, depending upon the athlete and the session. This represents workouts across three to five days and the sessions work on a specific aspect of fitness that we are looking to improve in that meso-cycle.

A periodised training plan should be broken down into macro-cycles, meso-cycles and micro-cycles. This then determines the individual meso-cycles. Each meso-cycle is built up of micro-cycles and each micro-cycle is a grouping of individual workouts. That’s the basis of any training plan, then. Now let’s delve a little deeper into a couple of concepts that will emerge as you work your way through a training plan: overloading and specificity.

Overloading

As a rider gets stronger, it follows that they can cope with more training. Therefore, in order to continue to give a stimulus to improve and build form, the training sessions need to get harder throughout the macro-cycle. This is called progressive overloading. There are a number of ways in which you can make a particular session slowly harder over time.

Volume – increasing the duration of sessions

Intensity – making the sessions harder. This in turn can be done in a number of ways: intervals can be introduced into sessions, intervals could be made longer or harder, or the recovery time between the intervals can be cut.

Recovery – as an athlete gets fitter the amount of time needed to recover from a similar session will be reduced. As a result, you can actually overload yourself by reducing the recovery between sessions in a training plan. However, this is a very difficult thing to get right and not something I would recommend unless you are experienced at following and planning training plans, and a very good idea of how you might respond.

An effective training plan will use these elements to slowly but surely increase the training load, allowing for a steady but consistent progression in fitness.

Specificity

We have already touched on specificity in the periodisation section, however it is worth revisiting. The key thing to remember is that specificity doesn’t simply mean replicating what you will need to do in a race or event. Instead, it’s about training specific aspects of fitness which, once improved, will lead to an overall improvement in performance in your chosen area. For example, a time trialist’s training plan wouldn’t simply involve riding ten miles a day as hard as they can. A far more productive training plan would look something like this:

Prep phase

General riding – get back into regular training after a break

Core stability work to improve efficiency on the bike

Focus on pedaling technique to improve efficiency on the bike

Base phase

Increase aerobic capacity to increase mitochondrial volume

Increase muscular endurance to enable the athlete to produce high torque for

20-30 minutes

Build phase

Lactate threshold training – improve athlete’s FTP

Speed endurance work to maximize mitochondrial output

Race

Specific race replications

Taper

Race

You should build specificity into your training plan in order to target improvements in your chosen discipline. This is obviously a very simplistic view but shows how different elements of fitness are addressed at different points in the macro-cycle, with a view to performing on race day. The reason coaches arrange a training plan in this way is to avoid one element of training affecting another.

For example, there is plenty of research that suggests training in a fasted state (i.e. first thing in the morning, having not eaten) is beneficial in terms of adaptation to endurance training. Therefore, as a coach, I might want to have a block of training where my athlete trains in a fasted state, but I also know from research and literature that training in zone three and above require glycogen usage, which comes from a limited store. As a result, I can’t have a rider doing efforts and burning glycogen if they haven’t eaten in the morning as they will be unable to effectively complete the session.

Therefore, I might schedule fasted rides in the ‘base block’, where they will be riding in zone two and below and predominately using fat as a fuel. The rider will then see the benefit of those fasted rides and to maximize the effect I will group all the base rides together – but once we move onto the next block, I will then set efforts in zones four and five and tell my athlete to eat a high carbohydrate breakfast to fuel the session as I know that is what they need to perform at their best. This approach is known as block periodisation.

Back to power meters

It is at this point where your power meter becomes so important. In my last piece we looked at the training zones and the physiological adaptations you can expect to see from training in each zone.

A power meter allows you to accurately measure which training zone you are in, enabling you to specifically work on a particular aspect of fitness as defined by the block of training you are currently undertaking. Without the ability to hone in on specific aspects of fitness, we can’t use ‘block periodisation’ in a training plan because we can’t be sure the right elements of fitness are being worked on at the right moment. Ultimately, if you want to get the most from any training plan, a power meter is an essential tool.

A power meter allows you to target specific areas of your

fitness. This article by no means covers all of the elements surrounding a

training plan, however it should have given you the key theory behind how an

effective training plan is put together. Each training plan should be specific to the athlete and to

the discipline they participate in – this will dictate, among other things, the

amount of time spent on each element of training, the length of the training

cycles, the zones trained in, and the balance between training and recovery.

ABR blogs are brought to you by Bloobo.com Website Builders.

What do they do?

Bloobo.com offers a wide range of services nationwide, all serviced from their offices in Derby.

Services include: Website Builder. Mobile apps. Marketing

They will work with you to design and build your website to match your brand, help attract new customers and manage social media and marketing consultancy.

Everything is designed for your brand and they offer great value whilst guaranteeing high quality.